Highlights

Like all historians, I’m interested in the stories people tell that help document change and continuity over time. Like most digital historians, I explore these stories using a variety of digital tools and new methods. In some cases, I’m interested in big-data approaches to analysis; network analysis, historical Geographic Information Systems (GIS), and computational text analysis help historians find patterns, fill gaps, and look for new questions in historical documents. In other cases, I work with interactive modes of presentation that afford historians new ways to present historical scholarship and to engage with new publics.

When digital historians make use of tools and methods developed by other disciplines for our analytical and presentational projects, we inherit the priorities and norms of those disciplines. My goal is to prioritize history’s disciplinary norms as the foundation for the design of digital-history tools and methods. My research trajectory as a digital historian, then, is focused on the concurrent and intertwined development of historical theory, digital-history tools, and historical methods. That research output takes four primary forms, from which I draw to articulate the individual elements of six major research projects:

- digital-tool and historical-method design with a variety of partners.

- Net.Create

- the digital-exhibit toolkit that anchors Community Archive Digital Projects

- other digital-tool development under the auspices of Design-Based History Research

- analytical digital-history projects in collaboration with other historians using my digital tools and methods.

- MMATCH as a guiding principle for collaborative text-based publications rooted in digital-tool design or digital public history (e.g. Sutton & Craig, DHQ 2022)

- digital public engagement projects in collaboration with academic and non-academic communities using digital tools and methods.

- History Harvests like Remembering Freedom, some of which are built on the Community Archive Toolkit

- Global Middle Ages Pilgrimage

- digital-humanities capacity-building and scholarly-communications research that explores how to better incorporate digital tools and methods into the academy.

These four forms of research output, and the six research projects rooted in them, have been shaped by a decade of experimentation with the boundaries of traditional historical research, teaching and service in both industry and as a clinical faculty member. Many of my projects combine one or more of these digital-history and digital-humanities practices, and all of my projects are shaped around collaborations that support digital-history endeavors at a variety of scales.

Past Accomplishments

My research has been supported by $2.25 million in grant funding (2 NSF and 2 private-foundation grants) and includes digital-history tool design (Net.Create), digital public history endeavors (History Harvests and community archives), and argument-driven digital-history research (Sutton & Craig, DHQ 2022; Craig & Diaz, AHR, forthcoming). Each of my digital-history projects integrates digital-history tool design and methods development in different measure and with various collaborators that extend the impact of my work to other subfields within history as well as beyond the field of history.

Future Work

Several in-progress projects extend one or more of the 4 strands of my research. The first fully integrates the collaborative work that Mixed-Method Approaches to Collaborative History has enabled, the humanities-focused network analysis that Net.Create offers, and my digital-humanities capacity-building research; planning for this Net.Create grant started in May of 2023 for a planned submission in October of 2023. The second is to take version 4.0 of the Community-Archive Template, which will be complete by the end of summer 2023, into new communities; two such community-archiving days are already scheduled for late October 2023 and I’m leading a team of historians, digital humanists, and librarians submitting an NSF Office of Digital Humanities Institute-of-Advanced Studies grant due for submission in August of 2023. Finally, I’m aiming to move the Global Middle Ages Pilgrimage out of IUB’s web platform and into an independent digital-public-history exhibit using an adapted version of the Community-Archive Template, bringing my medieval and digital-public-history skillsets together to make a scholar-sourcing platform for a new Global Middle Ages Pilgrimage that can be modified, adapted, added to, and localized for anyone interested in making medieval studies more publicly accessible.

Research: Digital-History Tool and Methods Design

Over the last 3 years in particular, I’ve developed an approach to digital-history research called Design-Based History Research (DBHR); the term reflects my history-specific adaptations of the Design-Based Research theory and practices common in Learning Sciences educational research. DBHR documents change and continuity over time in the context of a digital-history tool and the methods that best support the use of that tool in argument-driven history research. DBHR addresses the choices we make as a field about how we use new tools and methods, digital and traditional alike, choices that have long-term historiographic implications for our discipline.

Where argument-driven digital history starts with archival primary sources, DBHR treats the stages of a digital history tool and the methods historians marshal to use that tool as primary-source material. These “primary source” models for using digital methods in historical analysis drive a cycle of theoretically-motivated tool design and building which is then interspersed with small-scale testing intended to provide proof-of-concept theoretical models for disciplinary innovation usable by other researchers.

Network Analysis Tool Design as Historiography

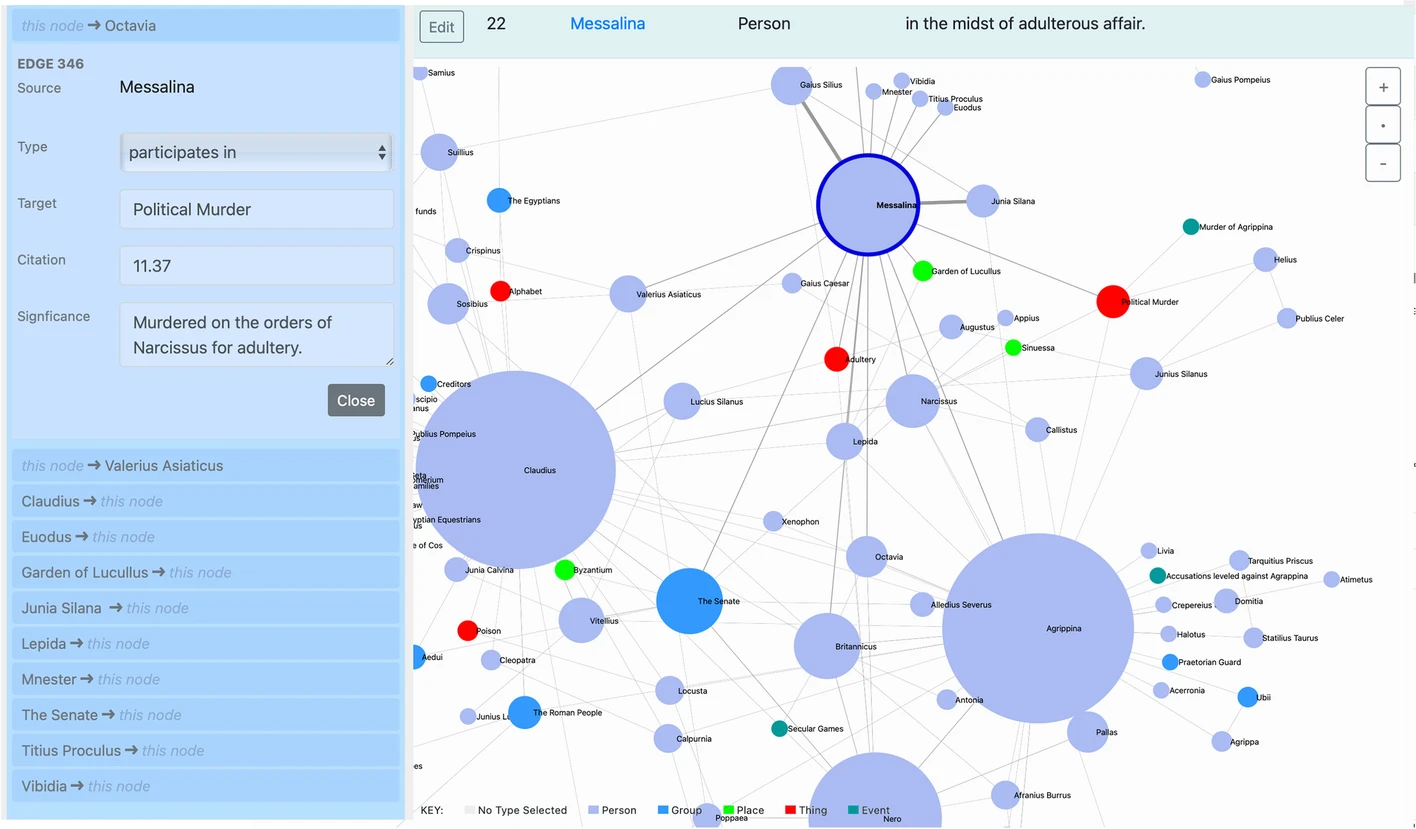

One research project well into its development cycle offers a microcosmic view of the integrated, longitudinal approach around which I’ve structured one arm of my DBHR practice. Net.Create is an NSF- and private-foundation-funded network-analysis tool designed specifically to address the gaps between purely quantitative and the evidence-based research needs of historians working with change and continuity over time.

The historical method asks us to tell evidence-based stories about trends and about the individual people who follow or buck those trends. From that angle, network analysis is a good fit for historians; in its most simplistic form, networks are an aggregate analysis structure built from the ground up around documentation of one-on-one interactions. We can visualize those interactions by turning individual actors into circles (nodes) and drawing lines (edges) between them for each interaction they have. Many of these dyadic interactions added together makes a network. As an actor participates in more interactions, its representative node gets bigger, showing us how important that node is to our overall story and drawing other closely connected nodes toward it in the network visualization.

Several quantitatively focused features of network analysis that are then emphasized by features in network analysis software make network analysis much less approachable for most historians. Networks in data science are often downloaded from large “complete” datasets with very rigidly defined relationships and no sourcing of evidence for interaction at the individual level. In some cases, the names of the network actors are even reduced to numbers because network analysts are more interested in generalizable patterns across many networks and less in the individual lives of the people who make up the network. Anonymized quantitative measures of networks drive network-analys with little consideration for citations, interpretation, argumentation and revisions or changes to the network relationships mid-project.

Net.Create changes that. Rather than simply accommodating a few changes to data-science network-analysis software, Net.Create’s features are designed from the ground up for historians through a process of iterative research outlined in a 2023 article at the Journal of Digital History, “Designing Our Digital Past: Anchoring Digital-History Tool Development in the Historical Method Through Design-Based History Research”. An easy-to-use hand-entry interface encourages historians working in teams with research assistants to debate relationships and their particularities, with required citations from primary and secondary sources for each interaction, filters that highlight gaps in evidence, and a flexible categorization system that allows researchers to assign multiple relationships to interactions and change interactions or agency types mid-project). With Net.Create, historians can grapple with relationships that can’t be reduced to simple, rigid definitions and do so in a piece of software built for historians by a historian.

As with archive-based book projects, DBHR projects are shaped around revisions and review processes. I’ve led Net.Create through 8 rounds of design revision since 2015, each one focused on a specific design feature or two that supports the humanistic use of network science, with testing and review at each stage. I took on the programming tasks for the first few stages of Net.Create’s revision from 2015-2018, which were designed around my own citation needs and collaboration needs with several close research partners and with internal funding from IU.

In 2018, Net.Create received a competitive peer-reviewed grant from the NSF, at which point I took on grant leadership for two rounds of revision with a team focused on adding both more refined support for the simpler historiographic-debate considerations (citations, note-taking, and treatment of date ranges and location data) and more complex categorization, concept taxonomy, and filtering. Three rounds of refinement enabled by the 2018 grant funding helped support independent use of Net.Create for research by faculty and graduate students both with and without IU affiliation.

In 2023, the Net.Create team successfully applied for another round of funding, this time from the NSF for $900,000 to support the development of several additional features for historians: provenance for each piece of data, to support further humanistic interpretation of data in the network; and significance rankings, to allow Net.Create users to rate the relative importance of a particular interaction in the network. While we identified these features as vital for historians, the 2023 NSF grant will first be used to help drive more equitable access to data literacy in middle-school social studies classrooms, a demonstration of the value a digital tool built specifically for working historians can have outside of the academic discipline of history.

Net.Create’s most recent rounds of revision have also been focused on methods design–in otherwords, insight into the best ways to shorten the learning curve experienced historians have as they connect their traditional historical methods skillsets to network-analysis skillsets and determine how and when they should critique or question the network analysis results of their data entry. These methods-development efforts have born argument-driven-history fruit in the form of a current research partnership with Dr. Collin Elliot and an undergraduate researcher that explores the role of gendered network formation in late-Antique Roman politics.

Any digital-history tool-design claims need to be vetted by reviewers and users. I’ve drawn on three separate approaches to make that possible for Net.Create:

- faculty and graduate student research workshops and consults to assess Net.Create’s value for humanities network-analysis research;

- in-classroom testing to evaluate the tool’s practical value for novice researchers

- expert-reviewer feedback through grants, peer-reviewed articles, and private-foundation use.

Independent use of Net.Create by humanities researchers outside of the more formal assessment channels I developed has also been a vital part of Net.Create’s design, review, testing and development process.

Finally, Net.Create is the site of ongoing private-foundation funded research-driven public-policy work. The Council for Public Liberal Arts Colleges and Lumina Foundation separately asked for assessments of their existing networks of activist and higher-education-policy world. In the case of Lumina Foundation, Ann McCranie, Kate Eddens and I are currently engaged in the second grant-funded round of analysis that draws on oral history, ethnograpy, and Net.Create’s debate- and citation-oriented network-analysis design to lay out the contours of Lumina’s last decade of activism and help them shape the contacts they make in higher-education policy strategy over the next decade.

Design-Based History Research as public history

In parallel with Net.Create, I’ve spent the last few years working in digital-public-history spaces with partners both on- and off-campus. The most rewarding and future-facing of those projects is a series of History Harvests, which collect and present a digital collection of artifacts that have historical significance but acknowledge that the physical objects need to remain with the families whose history they represent. These History Harvests started as service-learning digital-public-history projects rooted in classrooms; I organized and led 2 public collection days in 2019, helped with a third, and led the narrative-writing and digitization processes to launch all three digital exhibits in 2020 and 2021. The challenges and potential research opportunities that persisted across all of the History Harvests have since become a focus of my very recent and near-future Design-Based History Research.

One History Harvest in particular helped me identify a need for historical-methods design expertise in the community-archive corner of the digital-cultural-heritage preservation world: Remembering Freedom, done in collaboration with Dr. Jazma Sutton, a recent IU PhD recipient, and a descendant community of one of the largest pre-Civil-War free Black communities in Longtown, Ohio. Partnerships between communities like Longtown and university-based digital-history, digital-cultural-heritage, library-science and archival-preservation experts have generated a wide variety of community-preservation projects over the last decade. Many of these projects are driven by community preservation needs but shaped by cultural-heritage-preservation or library-sciences research priorities that privilege high-quality preservation and complex discoverability strategies. Working directly with the Longtown community on both preservation and oral history brought a historian’s eye to the issues that historically-excluded communities face as they collect, preserve and narrate the changes and continuity in their own communities.

The two most pressing of these concerns don’t have easy solutions. Community rights, access, and ownership needs are often at odds with scholarly preservation and research-discoverability goals. Oral-history release forms regularly transfer ownership of the digital assets to academic partners, which can strip community control over, and rights to, their own history. Similarly, while there are a number of tool kits that are free to use for the preservation of community cultural-heritage collections, many are built to prioritize discoverability for researchers rather than community-led narratives. At the same time, approaches to the design of a community-archive collection should be informed by, and help ethically support, the research practices of historians like Dr. Sutton whose life work has been to uncover hidden histories.

Solving these community-oriented DBHR challenges will require someone with both technical skills and an historian’s sensitivity to the needs of the people whose stories are being collected. Working with partners at the IXeM Collective and the Institute for Digital Arts and Humanities, and drawing on a variety of literatures focused on historically excluded communities, I’ve begun development on the Community-Archive Toolkit, which prioritizes low-cost community-owned platforms with minimal-computing requirements for building community public-history digital collections. The tool-kit includes a website template; video and online tutorials to use that template; and example release forms that offer a variety of ownership and discoverability options. With no high-end cameras or costly web hosts required for the toolkit, communities can choose to partner with an institution like IU or work independently to host their collections and maintain ownership of their work.

The Community-Archive Template is still in its early stages of the DBHR process, in that it has only seen three rounds of revision. I expect there will be additional challenges that present themselves as the MARCH and IXeM Collective undertake three more History Harvests with planned collection dates in Fall of 2022 and Spring of 2023 and collection launch dates in 2023 and 2024. In addition to filters and tags that allow community members to organize their collections by category–and more importantly, to show and hide parts of their collections for selective sharing with researchers and the general public–the Community-Archive Toolkit needs to be tested more broadly to ensure that it does support the balance between community ownership and research discoverability that motivated its initial development.

Design-Based History Research in digital-history method development

Both Net.Create and the Community-Archive Template are illustrative of my goal to foster disciplinary change and historical-methods innovation through my DBHR portfolio. For historians with similar questions but without my unusual skillset at the crossroads of advanced historial methods, theoreticaly motivated design, and digital tool building, these are insurmountable barriers.

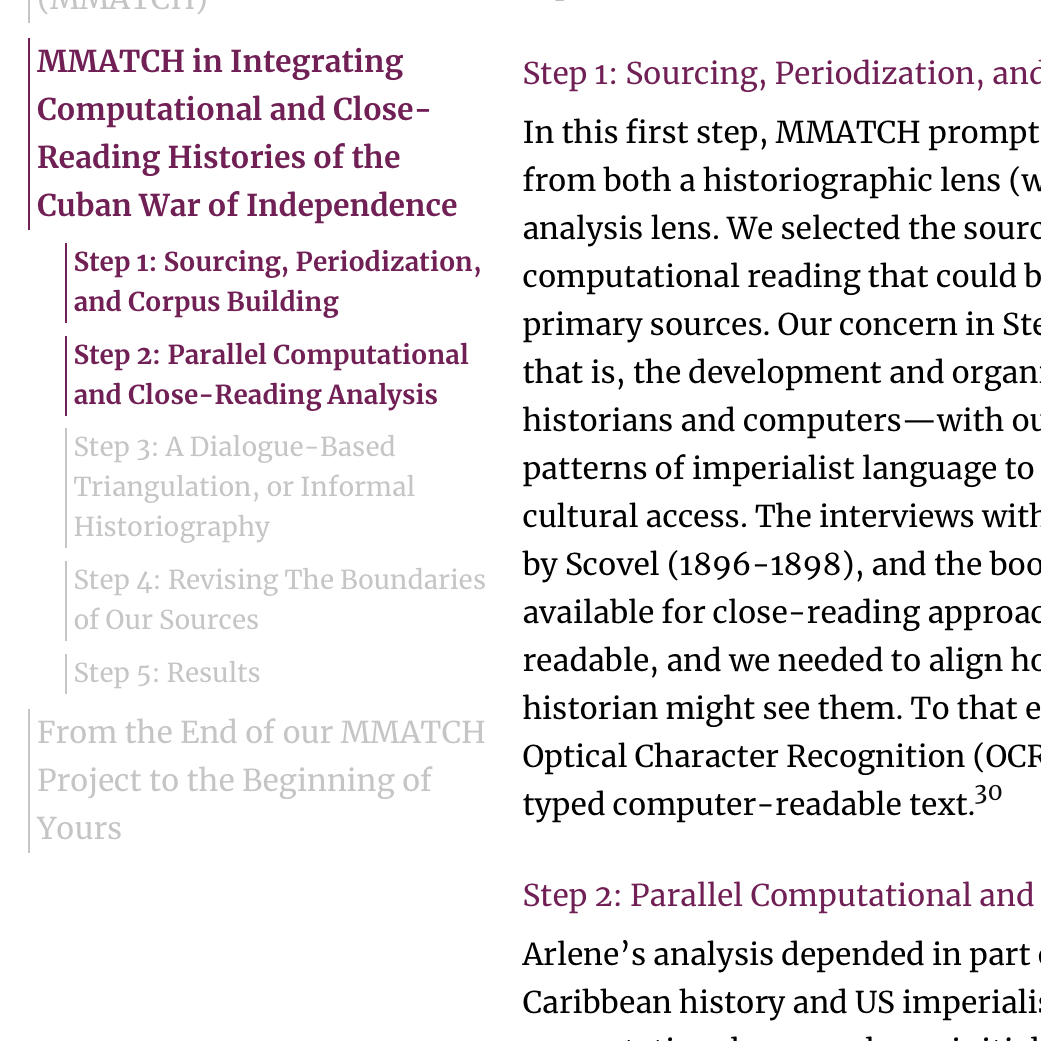

The final aspect of my work addresses these barriers through structured collaborations that articulate methods-driven approaches for using these digital tools as analytical and presentation platforms in the production of argument-driven historical scholarship. Social-science and hard-science disciplines offer a number of well-articulated methods for collaboration that offer repeatable steps and specific analytical pathways. History needs similarly well-articulated methods that accommodate the individual theoretical frameworks of each historian involved in a collaboration. We also need to account for the fact that, while interpretive hermeneutics make repeatabiity in historical research not only impossible but less-than-ideal, we would benefit as a field from a procedural guide for well-structured collaborative research. An article on the connection between the Longtown History Harvest and its historical antecedents, first-authored by Dr. Sutton, highlighted the need for a structured methods approach that helps historians position their individual scholarship in the context of a research partnership. A collaborative text-analysis piece currently in progress with Arlene Diaz will introduce the next stage of that structure: Mixed-Method Approaches to Collaborative History (MMATCH). MMATCH is a process through which historians can document the overlaps in interpretation and method that make collaboration a generative process for new historical research, and Dr. Diaz and I have identified the American Historical Review’s History Lab section as an ideal submission venue.

MMATCH is also the platform on which I have built a number of more traditional argument-driven history endeavors. In addition to a research partnership with Dr. Diaz, I’m also drawing on MMATCH to help organize and integrate two other projects. MMATCH has helped guide the analysis jointly produced by Dr. Eliott, Ms. Zafar, and me in our article on Tacitus’ networks. MMATCH is also the anchor for an in-progress grant that seeks to identify networks of potential partners for environmental histories of ivory with Dr. Jonathan Schlesinger; the prospective grant team met in late May of 2023 to identify federal funding streams and is on track for an October 2023 submission to NSF’s AccelNet program.

Teaching

When I began teaching history, my primary goal was to help students understand the skills involved in historical practice as a way to accommodate, synthesize and intelligently use the ever-increasing volume of communication they deal with, both personally and professionally. The high-level critical thinking and analysis we employ to deconstruct, contextualize and synthesize primary and secondary sources can be used equally well in support of a historical argument, to analyze a voting choice, or to justify an important business decision. In an early course evaluation, though, a student expressed disappointment that my assignments were too focused on supporting an argument with evidence. While I was thrilled that the student felt comfortable using a newly learned historian’s tool kit, I was also reminded that historical practice sometimes overshadows the wonder that comes with exploring a world full of new names, dates, and places. My ongoing teaching challenge is thus to both demonstrate the utility of historical practice and simultaneously communicate my awe of and enthusiasm for exploring the past.

Curriculum development at the campus level has occupied a portion of my teaching duties, at both the undergraduate and graduate level. Each of these curriculum-development efforts has centered on the ways in which humanities learning can be augmented by digital methods at the same time that we encourage students to question the assumptions and algorithms built into those digital methods. At the graduate level, I served on IU Bloomington’s Digital Arts and Humanities PhD Certificate creation committee in 2014. On my appointment as IDAH’s co-director in August of 2017, I developed the curricular and administrative infrastructure necessary to launch the program based on that 2014 committee’s design, including the recruiting and convening of a curriculum committee to oversee the development, submission and teaching of new courses to meet the program requirements, and advising prospective students. Since Spring of 2018, we’ve done individual advising each semester for 40 individual students, admitted 24 to the program overall, and awarded 10 minors and certificates. At the undergraduate level, I’ve been involved in the development of several undergraduate programs that center technical and scientific practice in the critical lens of humanities interpretation. ASURE, the program has been on offer for College direct admits since Fall of 2018 and includes a fall-semester introductory course, which I chaired a subcommittee to develop, and a spring-semester hands-on research course, for which I developed and taught A200 Digital Public History. These curricular-development efforts also include a committee seat on the College’s Undergrad Computing Task Force and its subsequent Committee on Undergraduate Computing in the College, which resulted in a Spring 2020 report that lays out concrete curricular programming, in several tracks, to prepare students for disciplinary-specific use of technology in service of their chosen humanities majors.

My course development is either oriented toward teaching digital methods for historical argument or is “digitally inflected” and uses digital methods where appropriate to support the learning of historical content in a topics course. As I develop or redevelop a course, I keep a single guiding principle in mind: history’s systematic approach to interpreting documents in service of rebuilding historical context and exploring change and continuity over time. While a professional historian can and should push the boundaries of that system in order to create new knowledge, our students often need scaffolding before they can be asked to use all of these skills together. This approach means each course has two practical goals for students: a learned independence that fosters willingness to make mistakes, which in turn supports the construction of open-ended historical argumentation. I emphasize classroom-based activities over lecture to give students access to expert guidance in class, so that guidance can shape their reading and research outside of class.

Service

The division between my service, teaching, and research is somewhat blurred when it takes the form of professional-development instruction and consulting for faculty and graduate students who have begun to explore digital methods in their own research and in their classrooms. I incorporate lessons from my tool building and digital-history pedagogy research into invited and research-conference talks, structured workshops, and consulting practices. These events help other faculty and graduate students hone their digital-methods approaches in disciplinary-specific ways. Over the years, many of these connections have become fully-fledged research collaborations, a pattern which I hope to continue in the future.

Outside of the integrated teaching-and-research service that takes the form of workshops and consulting, providing digital-methods service to IU Bloomington and to the Department of History means making space, both literally and figuratively, for digital arts and humanities methods at a departmental, campus and national/international level in a variety of service writing and committee environments. By contributing these professional-development and digital-humanities training opportunities, I can help bring perspectives on developing digital-methods expertise from the Department of History and IDAH to a broader audience outside of IU.

A number of national and international service projects bring my digital-methods expertise from IU to the history discipline more broadly. Two service activities take particular advantage of the digital-methods nature of my work in history. First, editorial service as a digital-history specialist has provided a venue through which I can help shape the production of scholarly knowledge in both digital history and the historical discipline more broadly. In 2017 was invited to participate in the “Arguing in Digital History Workshop,” a 2-day invitation-only workshop that brought 25 experts in digital history to George Mason University’s Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media (CHNM) to talk about challenges in the field. In 2021, I was invited to serve on the AHR’s editorial board as a digital-history specialist responsible not only for peer-reviewing digital-history scholarship but also for helping the editorial staff expand the journal’s ability to present the arguments made in interactive visualizations. Most recently, I joined the reviews-in-the-classroom team for Reviews in Digital Humanities with the goal of providing a venue for the next generations of digital historians to publish their work. Second, participation in the AHA’s Digital History Working Group has allowed me to provide support for colleagues outside of IU. The working group was tasked with providing guidance in interpreting the AHA’s digital-history evaluation guidelines to scholars, chairs and administrators working on tenure and promotion cases that include digital projects. In 2019, the AHA published a guide focused on communicating these findings to the AHA’s constituents, and I took primary responsibility for writing Project Roles and a Consideration of Process and Product, one of the central pieces of that guide.

Support for the digital work done by other faculty and graduate students here at IU has guided my committee and working-group commitments. To that end, I’ve focused on service duties that address the importance of IU’s digital and physical infrastructure in supporting digital methods, so that there is practical support available for faculty who would like to integrate digital methods or digital tools more broadly construed into their teaching and research. As co-director of the Institute for Digital Arts and Humanities, my service to the University has drawn on the history department’s goals and needs to help other humanities researchers and educators. In addition to fellowship administration and consulting for both faculty and student fellows, I work with my colleague Michelle Dalmau, and our research assistants and office staff, to manage several active speaker series and a weeklong Summer Incubator, which is designed to jumpstart 6 digital-methods research projects each year. In late July of 2020, we completed our third-year review, which is available publicly .

Beyond IDAH, I’ve also made it a mission to find ways to merge the technical needs of digital methods with the broad variety of concerns driven by researchers and teachers across the IU Bloomington campus. Work in virtual and physical spaces on campus and system wide, as well as contributions to the college strategic plan, have provided inroads for history to make its needs and presence known campus wide. At an IU-system level, I’ve provided infrastructure-oriented service as a Mosaic Fellow and on the Smart Classroom Working Group. In Bloomington, I’ve served as the faculty representative on the Bloomington Faculty Council Teaching and Learning Spaces Committee (2019-2020) and on the Bloomington Faculty Council Tech Policy Committee (2019-2020). These service commitments have given the Department of History input into the shape of IU’s future classrooms and technology needs across the entire system.

As Associate Director of the Medieval Studies Institute, I extended my administrative skillset from IDAH in service of the medieval studies community at IU. As part of that work, I spearheaded a digital-public-engagement project, a Global Middle Ages Pilgrimage that complicates the public image of medieval as purely Western European. The Global Middle Ages Pilgrimage matches pilgrimages from all over the globe undertaken between 500 and 1500 and maps them onto locations at IUB that serve a similar purpose. In the next phase of my Community-Archive work, I expect this will become a more robust digital-public-history research project.

Much of my service for the department clearly ties to teaching and professional digital-history development, to the research that supports those two endeavors, or to equity and justice concerns that derive from my digital public engagement work. Building and then maintaining the department’s web site from 2015 to 2021 offered our department a communal platform to promote public engagement with our research and teaching activities. In the last year, service as the chair of the department’s Diversity, Equity and Inclusion committee offered the space to reshape how the department communicates our dedication to making the discipline more equitable.

A coda (or: “What’s next?”)

While much of my work feels technical in nature–designing software, annotating the data drawn from primary sources, working with community archiving platforms–the design choices I make in each of these cases are rooted in a commitment to the values of a historian. The technological considerations of a world dominated by smartphones and digital archives should accommodate the needs of the people operating in that world. The value of an appointment that melds the digital and the historical is in its ability to communicate with living people. Guiding the design of digital tools and methods to explore historical documents is part of the meaning-making in which historians engage. As such, like the work argument-driven historians produce, my Design-Based History Research Agenda will continue to contribute to the creation of new knowledge about our collective past.